Meet Jill Waterman! Photographer, Writer & Rad Human (from B&H Photo)

We Peppers feel so fortunate to meet and build friendships with the most incredible people in the photography industry, and Jill Waterman was no exception! Jill is a wildly talented photographer, as well as a Senior Creative Content Writer at B&H Photo and Video. B&H have been a huge support and sponsor of Conference + Chill, The Virtual Photo Gathering and we’re pretty freaking lucky.

Stacey, our fierce and feisty leader, was inspired after joining Jill for an epic interview back in March so she asked if we could turn the tables and get a peek into Jill’s story! Stacey and Kelsey (Pepper’s Public Relations Executive), really dive in with Jill in Part 1 of this interview and it’s jam-packed with photography gold. Everything from her experience shooting night photos with film, to her time studying art in Paris, to the story behind some of her most well-known projects.

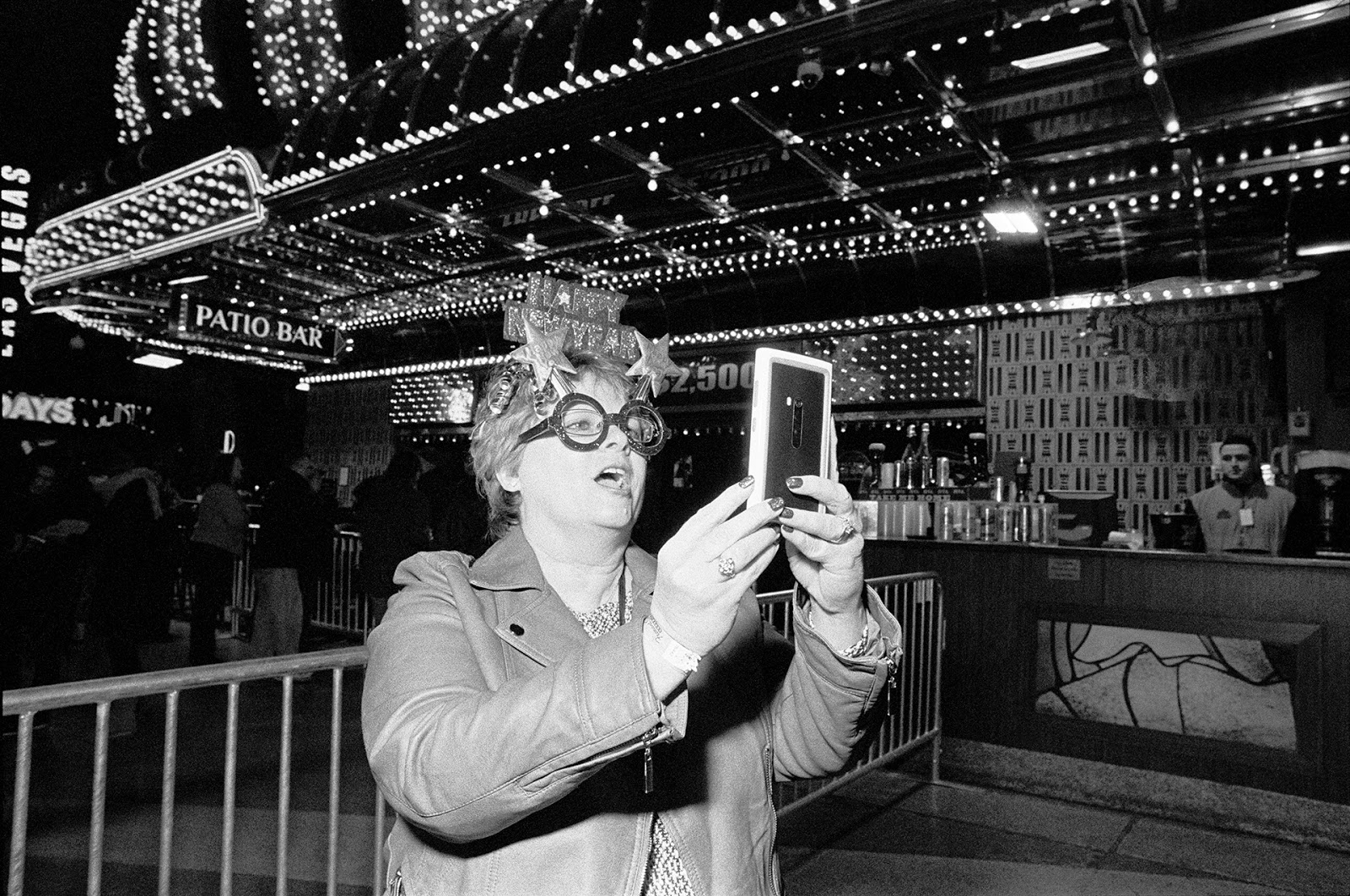

New Year’s Eve Selfie at the Freemont Street Experience

About Jill Waterman

Jill Waterman has been a team member of the B&H Explora blog since 2015. She originally studied printmaking in Boston and Paris, and after more than a decade as a photo editor, she added writing to her list of talents as an editor of custom publishing projects for Photo District News. Her first book, the technical volume Night and Low Light Photography, was published by Amphoto in 2006. The information she shares over on the B&H Explora is invaluable, and her personal projects, including her New Year’s Eve Project, and the train station pictures used in her Explora story Lessons on the Rule of Thirds, are incredible.

Stacey confesses that she was fascinated with Jill after their first chat and that we just want to know all the cool kids! Speaking of fascination, let’s jump in!

Interview with Jill Waterman

J: You know it’s funny because, as a kid, I was fascinated with biographies. I read every single biography in the library and it was only recently when I started writing the sort of biographical stories I do for Explora that I realized there was a connection. It’s one of my current favorite things to do.

S: It’s come full circle. Did you used to look at people and wonder what their story was?

J: I think so. Actually, my father used to do that. One time, we were sitting in a car waiting for my mother somewhere and all of the sudden—he was the tall, silent, never knew what he was thinking type—he said, “Gee, do you ever look at people and wonder what their story is?” I was shocked by that, because one would never have known this otherwise, and it really stuck with me.

S: I love how doing what you do now is so much a part of you. When we drive by little towns and the cute little houses in the woods, I always wonder: Who lives there? What do they do? How did they end up there? What’s important to them? It makes me so curious.

K: I’m the same, but I can’t just go around asking people what their deepest passion is or their biggest fear! I think like your dad…

S: Do you think that’s also part of why you’re attracted to photography?

J: Yeah, definitely. It’s interesting. One of the things that you asked about was my photographic style, and it’s sort of counter to a lot of what photography is supposed to be.

It’s supposed to be about reality and objectivity and everything, but what interests me in photography is being able to show what’s invisible—to show things you can’t see in reality.

Extending time through night photography or messing around with shadows and reflections and things like that, and transporting somebody to a different space. That’s what interests me about photography, not the sort of documentary realism stuff.

S: The little bit of fantasy in life.

J: Yeah…or surrealism too. With my New Year’s series, that kind of stuff happens a lot where people are so wrapped up in the moment. It’s like there’s almost this spirit that comes out in the pictures.

Those are the pictures that really succeed to me. It’s beyond what is just in front of you. It’s hard to get. It’s definitely not something you can get in every frame, but when it does happen, it’s magic.

S: That’s probably the best description of “How would you describe your creative style?” With so much heart and so many layers. Are you feeling it first or are you seeing it first?

J: It’s sort of hard to predict. With a lot of my pictures, it’s not something I can plan. It’s like synchronicity. There are times where I’m in the moment and I definitely have a sense that there’s something happening. Oftentimes, the pictures that I’m really confident about end up falling flat, and pictures that I really didn’t anticipate as being anything end up as something good. It’s sort of a tricky game that way, which is what makes it fascinating.

S: Do you feel it’s because you’re not quite sure what you have until you bring it up on your computer screen, and then you can really see it in detail? Or, when you go to edit, you can bring up those shadows, and play with it a little bit and be free? I always find a photograph is a sketch and then after I edit it, that’s my painting.

J: Right. The other aspect with my New Year’s pictures and a lot of my older night photography is that I’m shooting with an analog camera on film. I used to do really long exposure night photographs where the shutter would be open for an hour or two.

That’s not something you can predict at all. It would take several days to get the film developed, and maybe you got something or maybe you didn’t. With that kind of photography, you can only do a handful of pictures every night.

A lot of times, I’d get my pictures back and nothing would turn out, and I’d be upset. But on the rare occasion there was something magic, it was just…Wow.

It becomes really experiential. There’s this one picture I took—this colour landscape in a rural area in upstate New York where there was a red barn with a beautiful New England-y kind of look.

I put the camera on a tripod, opened the shutter, went for a walk, came back, took a look, decided to extend the exposure, and left it for almost two hours, I think. It was on a slope and there was a hill in the background and in that time, there was this ground fog that came up from the valley.

By the time I went to get my camera, there was literally a line of ground fog up to my knees that was totally opaque. I couldn’t see my feet, but my camera was on a tripod a foot or two above it. I was like, “Wow. This is going to be interesting.”

It gave the picture this really soft focus look all over. It’s not something you could see. It was the cameras that did the seeing.

S: You can’t even plan for that. It’s being open to whatever happens.

K: I love that. It’s like capturing the moments between the milestones. Like, you go to shoot a sunset, but instead you capture this tiny moment before that you weren’t anticipating, or if you’re a wedding photographer, you’re ready to capture the bride walking down the aisle but then you capture this moment of her wiping a tear from her father’s face or something. When you’re describing it, that’s what I think—just capturing these tiny little intimate moments that you weren’t planning on.

J: Yeah. When I’m photographing people on New Year’s, I like to catch them unaware. They see me with my camera and because people’s sophistication with photography has grown, it’s gotten progressively more intense over the years. I’m always trying to catch them before they see me, or they will fall into the classic…or not even classic..just the expected pose. Often that happens before I can get the first frame.

I end up playing this cat and mouse game—because I’m shooting with an analog camera with a totally manual focus, and it’s dark, I spend a lot of time just playing with the lens trying to make sure the focus is sharp. Sometimes they get annoyed, or they don’t understand what I’m doing, but that extra time frame makes them relax, or forget about the grip-and-grin and get back into character, and then I can get the picture. It’s an interesting phenomenon.

S: I love when you look at a photo and you can feel it. When it’s real.

J: Yeah. It happens a lot, and I’ve also encountered a lot of really interesting cultural differences when travelling to different countries to photograph New Year’s… Americans are the worst. They have so many expectations. People sometimes think I’m the event photographer, and they want to see the picture on the back of my camera. I would turn the camera around and say, “No. Give me your contact information. I’m happy to give you a copy if it turns out, but it’s going to take some time.”

Whereas in other cultures, people are so much more in the moment, and not expecting there’s a photographer to capture them looking their best. It’s fun going to other countries; it definitely becomes more interesting.

K: Have you noticed how people celebrate New Year’s Eve in different cities and countries? And have you noticed changes to celebrations over time because you’ve been doing this project for 37 years?

J: Yeah. It’s had a really interesting arc. When I started it was 1984, I was in Paris and after having so much fun making pictures, I decided to make it an annual project. I had no idea that 15 years later this thing called the Millennium would be happening.

After the Millennium, things died down a bit, and I wasn’t sure about my purpose or what to look forward to. But then I started getting tuned into places with these ritual celebrations.

In the United States, the classic example is Philadelphia—they have this event called the Mummers Parade, which is part of an old English custom to dress up and perform. It’s sort of like New Orleans’ Mardi Gras, but in Philadelphia it happens on New Year’s Day.

Then, in the Bahamas, there’s a similar kind of celebration called Junkanoo, which comes from an African slave tradition.

In Cape Town, South Africa, they have a similar tradition called Tweede Nuwe Jaar, or Kaapse Klopse, with a minstrel parade on January 2nd. It originated with slaves, who had only one day of rest during the year, because all the slave owners were drunk and sleeping off their New Year’s hangover.

The slaves started their own celebration with costuming, and music, and dancing.

There are so many different factions of people who celebrate in these ritualistic ways in different pockets all over the world and it’s been fascinating. I’ve started documenting these rituals in recent years, which has given the project more legs.

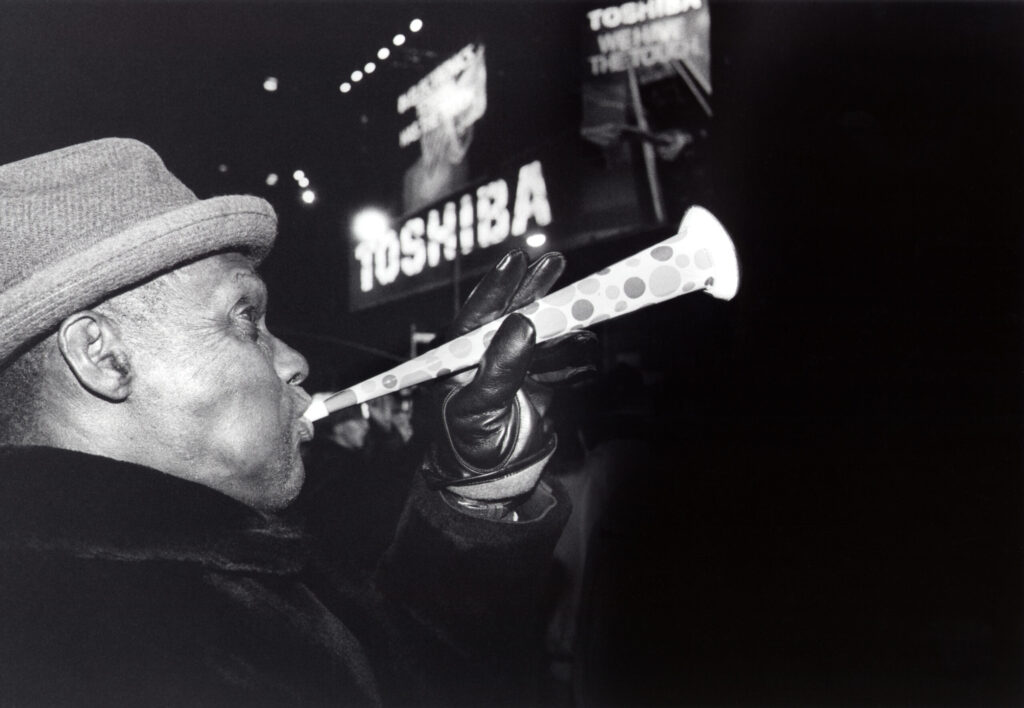

British Bobbies in a Shaving Creme Fight

Is there one celebration that you know of that you haven’t been able to do yet? That once Covid is over you’re like, “I’m going to get this one.”

J: There are a lot. I haven’t done a deep dive into research yet, but New Year’s traditions are significant in Japanese culture for several reasons. Some of the remote islands have important celebrations, and I haven’t gotten there yet. That’s one place I’d love to go.

Russia is another place where New Year’s is an important celebration, because it’s secular.

For many years, it was the one holiday people could celebrate because there was not a religious tie. There are a lot of places that are still on my shortlist, and whether I’ll get there or how I’ll get there is yet to be determined… It’s still a work in progress.

One really great celebration in India that I have photographed is called the Cochin Carnival, and it’s held in an ancient Portuguese fishing port called Fort Kochi. I learned about it totally by chance in a tiny newspaper story. The Carnival was started by a local government official in 1984, as a way to involve everyone in a free and equitable celebration for all people, and it takes place during the last half of December. For New Year’s Eve, the organizers build a huge effigy that’s at least 40 feet high, which they set on fire at midnight.

And, the only place I’ve photographed more than once is New York City—I’ve documented New Year’s Eve in New York three times—1986, 2011, and 2021. I decided to stay in New York this past year due to COVID, I felt it would be the safest option. I have a good friend in the NYPD, so I had pretty good odds for getting access to Times Square, even though it was off-limits to most people. But making pictures this past year was very challenging as there was very little of the energy that I generally feel building throughout the night. There were a lot of people circulating around midtown, outside the barriers to Times Square, and I made some good pictures there for an hour or more, but once I got into Times Square itself the scene was quite bizarre. There were two big stages with musical acts performing, but barriers for social distancing were set up all over the place, and people were assigned to little pods, so you couldn’t really wander around. Then, after the countdown started, I stepped around the barrier I was stationed behind to get a better angle on pictures of midnight.

To Be Continued

We’re going to wrap Part I of the blog right here, but let us tell you, Part II is going to be just as full of Jill’s incredible life. Make sure you check back in June for the second half of this epic interview with Jill Waterman of B&H Photo and Video!

Check out more of our rad Pepper blogs when you have a sec and hit us up if you’re looking to take your photography biz to the next level—it’s what Peppers DO!