Back in May, we released Part I of Stacey and Kelsey’s interview with photographer Jill Waterman, Senior Creative Content Writer at B&H Photo and Video. Jill is such an incredible photographer and all-around badass that we just couldn’t fit the whole interview into one blog.

In the second half, we’re going to continue learning about Jill’s adventures in Paris, photographing for her New Year’s Eve Project, and the super casual tidbit of when she became friends with a gentleman who had known Picasso and said he wished he was still alive to take Jill to meet him and show him her photographs! No. Big. Deal.

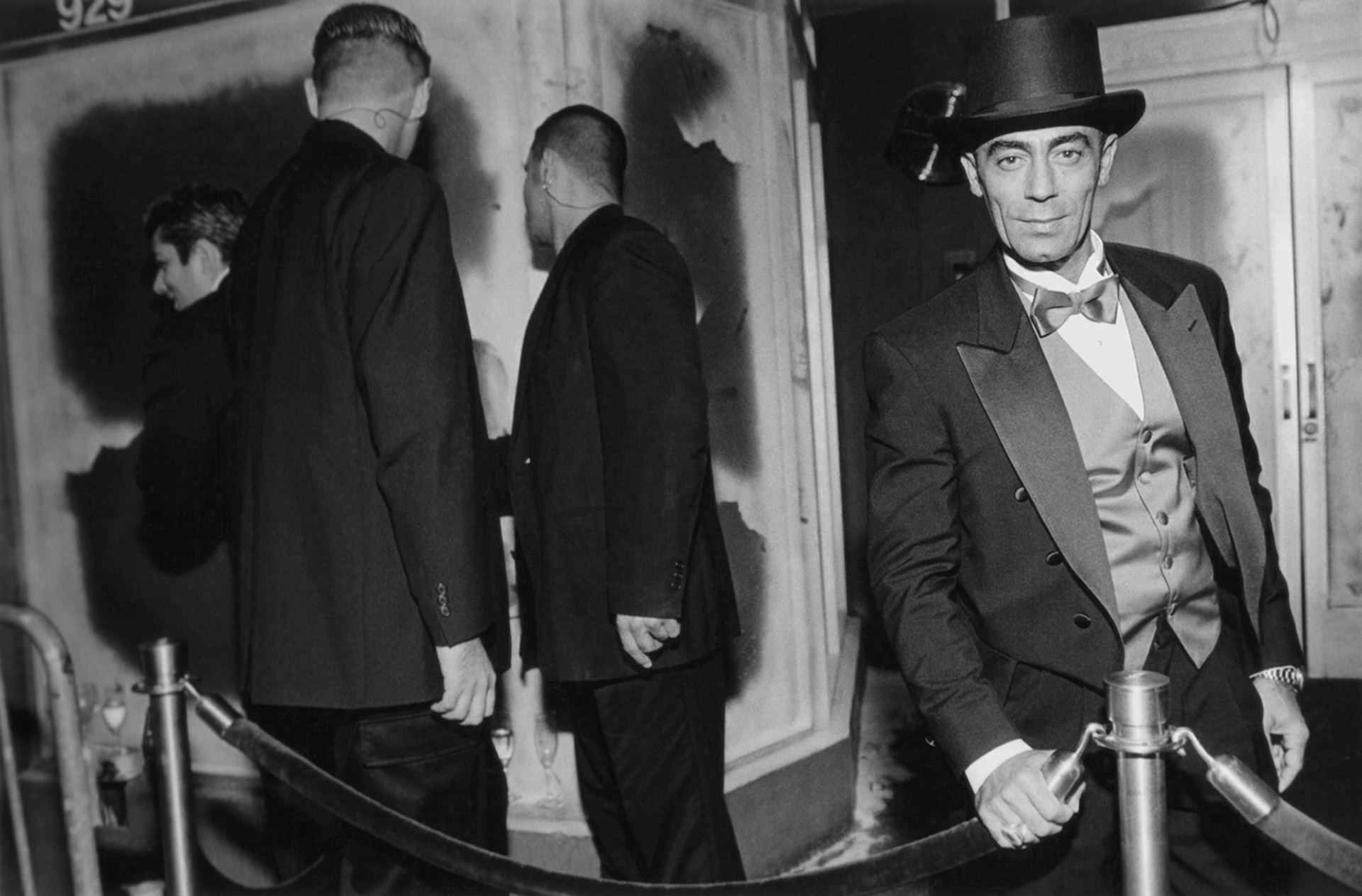

Doorman at the Velvet Rope, B.E.D.

Part II of our Jill Waterman Interview

S: So when you studied art in Paris and caught the photography bug, what art were you studying originally? And do you still create in that form?

J: I was a printmaker before I was a photographer, and I was doing photo printmaking and photo etching. I had picked that up in college, and I had studied French throughout high school and somewhat in college. I wasn’t really fluent, but I had enough French that I thought, “Well, if I move to Paris, I could work in a printmaking studio, and I could perfect my French.” So that was the idea. I had applied for an artists’ fellowship at the Fondation des Etats-Unis that included this amazing artist’s studio, and I ended up getting short-listed. I didn’t get the fellowship, but they said, “If somebody backs out, you’ll get the fellowship. But if not, we could rent you a studio at a very low cost.” So I decided to go for it and made plans to work in this traditional Parisian printmaking studio on weekdays. There was also a darkroom in the basement of the Foundation, which nobody had used in years. So I cleaned it up and started working there in the evening, and offering photography lessons to other residents. I had also signed on to do a degree at the University of Paris, which allowed me to get a student visa. I had also found a job as a cleaning lady for this artist couple to give me some pocket money, so I was way overtaxed with what I was doing.

S: And you slept two, three hours a day?

J: Yeah, well, when I caught the photography bug, it was actually a mistake that it happened. I was out photographing with film, because it was 1982. I was photographing a merry-go-round and the film broke midway through the role. I knew there was a weird double-exposure thing that happened when the film broke, so I decided to go home and remove the broken piece of film and develop it. I got this really cool multi-exposure photograph, so I fell into doing these multi-exposure photos where the whole roll of film was one continuous image. And it just blew my mind—I was so obsessed. I practically did not sleep for months. And, at the same time, I was still working with printmaking and etching plates with nitric acid.

One night, I was in the middle of etching plates with acid, and a friend came over to invite me to go out. I pushed the tray of acid under a table, and when I came back late that night I had forgotten it was there, and it sat in my room for nearly a day.

The next afternoon, after I went down the hall to the bathroom, I suddenly smelled the acid when I came back. I quickly bottled it back up, but I ended up getting pretty sick a few days later. It really gave me a wake up call that I had bitten off way too much and had to cut back. Printmaking—especially photo printmaking—is a very physical endeavor. So I decided that the photography held much more promise and it also allowed me to be much more prolific. So I just put the printmaking aside. I’ve done a little bit in various forms since then, but not recently. I would love to do other types of art but right now, the time isn’t there.

S: It’s always the case. But it sounds like that was such a magical time to be in Paris and being surrounded probably by other artists or other people who are interested in what you’re interested in and passionate about the same things, and to be able to experiment like that.

J: Yeah, not to mention, the couple I ended up working for—an elderly Spanish artist named Manuel Angeles Ortiz and his French wife Brigitte, who was like 20 years younger. Manolo, as he was known, was a friend of Picasso’s.

S: Get the fuck out!

J: He was a very significant painter, and a childhood friend of the famous writer Federico Garcia Lorca, and he had also been a friend of Picasso’s. Manolo had cancer and was in failing health, so I started helping him make prints of his own work in the last year of his life. One day he asked to see my work, so I brought him some of my photographs and he said, “If Picasso was still alive, I would bring you to meet him and show him these pictures.”

I mean, can we just sneak in here and say HOLY CRAP—freaking Picasso! It’s pretty incredible that Jill’s story includes something as amazing as this. Photographer Jill Waterman and freakin’ Picasso…Okay, back to it!

J: Yeah, this man was just incredible. He and his wife became practically surrogate parents for me. But then, when they went away for the summer, I didn’t have work. A friend told me about a family who was looking to hire someone to clean their house in exchange for a free apartment. When I phoned the gentleman and spoke with him, things were starting to sound familiar and I realized it was Brigitte’s brother, who I had previously met at their house. I mentioned this to him and he immediately gave me the job. That’s when I really knew I was in the right place at the right time in Paris.

S: Don’t you want to tell the young people, “Trust me, go on an adventure, take a risk. Go and do this thing, and have experiences. Don’t worry about having this thing?”

J: Yes. I am so happy I did that when I was young. After that, I ended up moving to New York City, where I studied for two and a half years to get my Master’s degree in photography. When I was leaving graduate school, I made the decision that I didn’t want to work as a commercial photographer because I felt like I would be locked into making pictures for other people, and it would not give me the freedom to make my own work. So I had this idea to find a job in the photo industry that would allow me to make money. I got a job in the stock photo industry in the late 80s through the 1990s, during the golden era of stock, when the field was just exploding. I worked one-on-one with all these photographers who were making a lot of money. I advised them about what to shoot, came up with shoot plans, and tried to help them shoot marketable imagery. I did a lot of research on the types of images that they were shooting and how to translate marketable concepts into visuals.

And then the stock industry fell flat. Getty bought everything, including the agency I worked for, so after 15 years, I ended up getting a buyout. I worked as a freelance producer for royalty-free stock for several months, and then I stumbled onto this opening to work for Photo District News (PDN), which had just started custom publishing a magazine for the American Society of Media Photographers. I was hired part-time as a writer, and then the editor that they had hired quit midway through the first issue, and it landed in my lap.

All of a sudden, I became a text editor, and I basically learned on the job. I very quickly discovered that there was a lot of commonality between picture editing and editing text, which I had never thought about, but somehow there was a connection that made the transition easy for me. I ended up being the editor of two different photo publications and a lot of other custom media and event projects, which kept me burning the candle at both ends for a dozen years.

Eventually, a friend who worked at B&H encouraged me to submit my resume for a writing position there and, within a matter of months, I had an offer.

I started out at B&H writing up product SKUs, which helped me to understand how the company worked from the bottom up. It’s a really tough job, but it was interesting and valuable. And then, after six months, I moved over to the blog, and I’ve been there ever since.

K: What’s been your favorite interview to date that you’ve done for B&H?

J: I have so many favorites, it’s always hard to pick. But one of the first long-form biographical narrative pieces I did was for a Mother’s Day piece. We were looking for content ideas that we could run to celebrate mothers and I knew the work of this photographer based in Boston, named Rania Matar, who makes portraits of women and children. I reached out to her and she agreed to an interview. She’s so well-spoken and it was incredible, the way the interview evolved into a story. And it became very…well, not easy (because writing is one of the hardest things I’ve ever done) but I was so happy with the way the piece turned out. It’s a beautiful story about her being an architect and a mother who started photographing her children as a hobby while she was pregnant and then picking up on photography and it becoming more and more important in her life. And now, she’s a full-time photographer with an amazing career. She got a Guggenheim Fellowship a couple of years ago and she’s photographed all these different aspects of children, teens, women, mothers, and daughters—all focusing on women. At some point during the interview, I learned that she lost her own mother when she was very young, so the hook became this idea of seeking the mother she lost through her photography, which was very powerful.

Another inspiring interview I’ve done was with Katrin Eismann. Her nickname used to be the Photoshop Diva. She’s just insanely talented, and she’s an amazing educator and has a fascinating story. She’s a master of reinventing herself, which is something I’ve always felt is really important. It’s something I tried to do when my stock photography career ended. It’s like how do you land on your feet? You just have to jump in and reinvent yourself.

S: Have you discovered someone new recently, or someone young, or someone who hasn’t been in the industry very long that just completely blew you away?

J: I feel like during this past year with COVID, it’s been really hard for me to get excited about much. But, there’s one story that we just published. It’s not about a new person in the industry, but the approach to the work was really inspirational. It’s a story about this advertising photographer I know, Chris Crisman, who came up with this concept of virtual production shoots during COVID, and he’s been doing that for the past year. Some of it is assignment-based work, but he’s also been doing these personal shoots. His pictures are all very highly composited lifestyle portraits shot in the studio with landscapes or backgrounds that are shot on location. He’s recently been doing virtual shoots internationally, including shoots in, like, six different countries over the past several months.

It’s become a way for him to be able to shoot these scenes without having to travel, while also keeping his cast and crew at low risk for the virus. It’s also allowed him to explore a whole different way of communicating. Some aspects of these shoots are very complex, but there’s also a lot of efficiency built into them, because, when working virtually, you have to plan so much out in advance that it takes the guesswork out of what’s going to happen during the shoot and in post. During our conversation, he said this one thing that I just loved:

When planning for a shoot, a lot of decisions tend to get left to chance. You’d just say, ‘We’ll figure it out on the shoot,’ which is the equal but opposite of, ‘We’ll work it out in post.’ But in a virtual shoot, pre-production becomes a final decision-making process.” — Chris Crisman

S: Did B&H or you personally have to pivot in any way during the COVID-19 pandemic? I mean, who didn’t in 2020?

J: Yeah. I mean, B&H, as a company, always had a very strict work ethic about everyone working in the office. There was absolutely no work from home, no remote work capability. And then COVID came along and with it, lockdown. So they had to very quickly figure out everything in terms of the IT. My team? We, as writers, really don’t need to be in the office. We do better when we have more time and space to write and think and work on our own. So we were pretty comfortable making that transition.

But the thing that became very interesting was the fact that the store shut down and—all of a sudden—the only lifeline the company had to the customer was through things like the blog and the fact that we were producing content that was being refreshed every day to let people know what was happening.

We started writing stuff about work from home. I mean, certainly all of a sudden all these people were ordering lots of gear to beef up their home office. The store was closed, but luckily the warehouse was able to remain open as an essential work situation, and they set up all sorts of safety measures to make sure the workers there were safe. All of a sudden, our team had this light shining on us where previously, people didn’t really understand what we did. “Oh yeah. We write stuff.” So overnight, we became the face of the company and a lot of people started turning to us and asking us to produce content that could be used in different ways.

So for our team, it was very beneficial in a very unexpected way. And luckily the company did pivot very quickly to put out a message to customers that we were there and we were supportive. It gave us an opportunity to reinforce B&H’s unique message of being all about the customer.

And so it allowed us to really hone in on that message. And, thankfully, things have worked out okay for the company as restrictions have loosened up.

S: The only thing we didn’t talk about was your book.

J: Oh, right! So yeah, the book was a very interesting outgrowth of my job at PDN because at the time a sister company to PDN was owned by a big publishing conglomerate. And we had a sister company, the book publisher Watson-Guptill, which included photography books. They were looking to do a branded series of books called PDN Pros. And so they came to me and asked if I wanted to write a book. My specialty has always been night photography. I’ve always joked that, ‘Well, I have a day job, so I take pictures at night.’ But it’s more than that; it’s my interest in capturing things that you can’t see, capturing the invisible, doing long exposures. That’s always been a fascination for me since I started making pictures. The New Year’s series is one aspect of that. Some of my earliest night photographs were portraits of people outside at night, where they had to sit still for a minute or more, sort of like the early photographic portraits where the photographer put a collar around the subject’s head so they wouldn’t move.

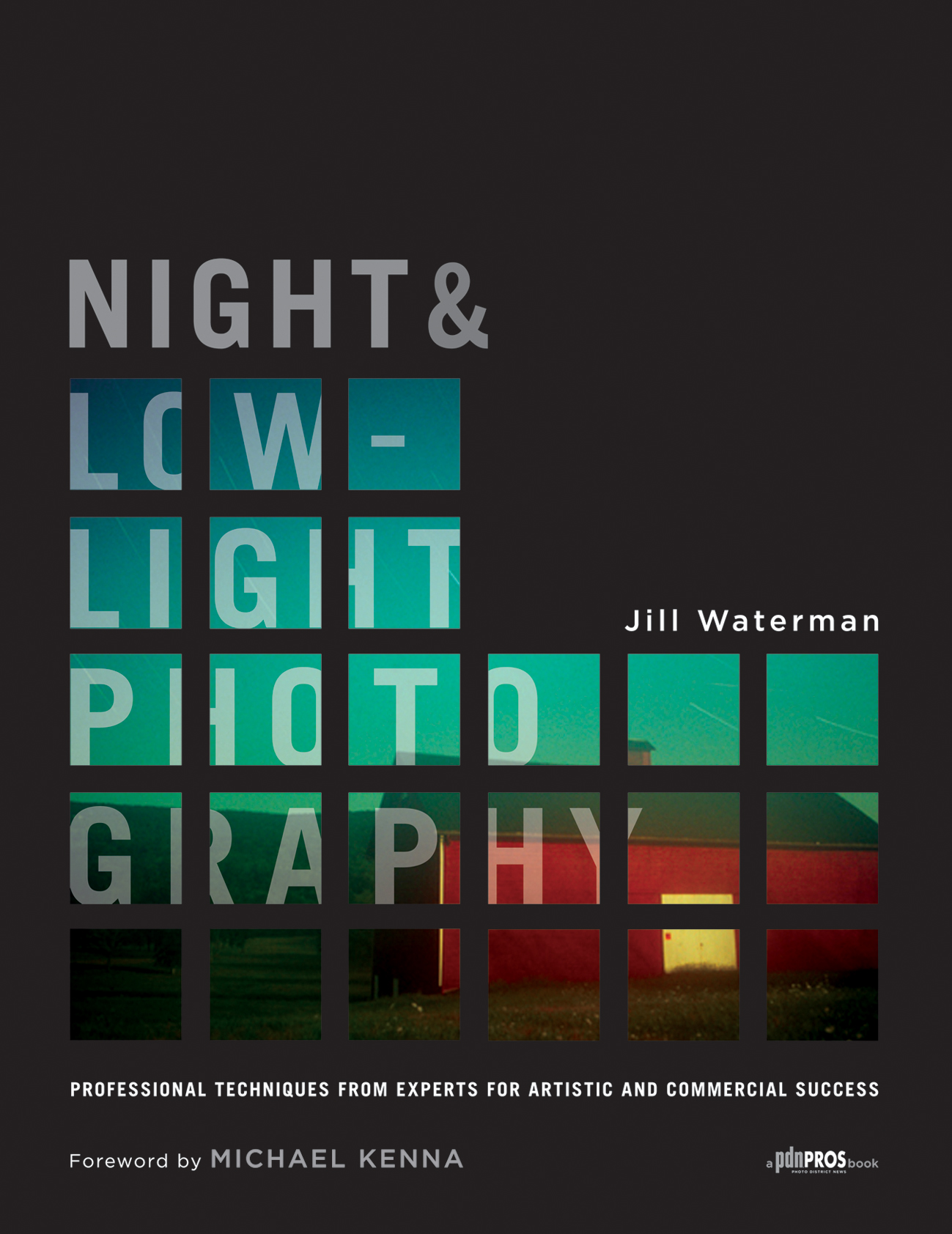

So anyway, I was presented with this opportunity, and I came up with the idea to interview 30 photographers—it turned out to be 29 photographers and myself. I don’t know how I came up with that number, but it made for a pretty ambitious book, titled Night and Low Light Photography: Professional Techniques from Experts for Artistic and Commercial Success. I interviewed each person about their processes and techniques, spanning both film and digital. I started the book in 2006, and while digital was pretty prolific by then, night photography was still on the fringe because of image noise during long exposures, so a lot of night photographers were still shooting film. So I covered everything from large format film to digital. At that time, digital was changing so rapidly, that became the hardest thing—to talk about digital in a way that wouldn’t get dated.

On top of the technical aspect, I’ve always been interested in personal processes and how people adopt specific processes to go from point A to point B, and how individual that is. The book ended up being about nine chapters long, focused on different aspects of night photography, from black & white to color, film to digital, landscapes to people, to weather, the moon, the stars, and so on.

S: So what’s next? You’ve done so much.

J: Oh boy. Yeah. Well, the one thing I haven’t done is a book on my New Year’s Eve Project.

I’ve done some media appearances, and I’ve been pretty fortunate with press about the project over the years. It always tends to be something that people are interested in on New Year’s. I’ve actually been trying to focus on writing a memoir to capture some of my experiences about being in these places, and planning for trips to these places, and to merge text with the photographs.

And seriously, we can’t wait for the day to see this book!

I think ‘mesmerized’ was the word that Stacey used during this interview. And when Jill apologized for rambling, Kelsey said, “It doesn’t count as rambling when you live an extraordinary life,” and we couldn’t agree more. We are inspired by this woman, similar to how she was inspired by Katrin Eismann, and how she reinvented herself. Jill truly has lived an extraordinary life, adjusting to her current circumstances regarding living arrangements and the opportunities that have presented themselves. She has risen to meet the challenges and has reinvented herself as she’s gone along and created an amazing adventure while doing so. We’re so honoured that Jill has shared this beautiful story with us.